Jan. 31, 2018 Press Release Biology

Running away from carbon dioxide: the terminal connection

Like us, fish need oxygen, and swimming through a patch of carbon dioxide turns out not to be a pleasant experience. Instead, they prefer to avoid carbon dioxide altogether. In experiments published in Cell Reports on Jan. 30, researchers at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Japan have discovered a neuronal pathway that makes this behavior possible.

High levels of carbon dioxide are dangerous. Many animals have built-in avoidance behaviors that take over when necessary and people can even experience fear and panic attacks when too much carbon dioxide is in the air. In efforts to understand the neurobiology behind these types of responses, the team at RIKEN turned to zebrafish-animals that are useful because the larvae have easy to characterize behaviors and because their transparent brains make imaging neuronal activity a breeze.

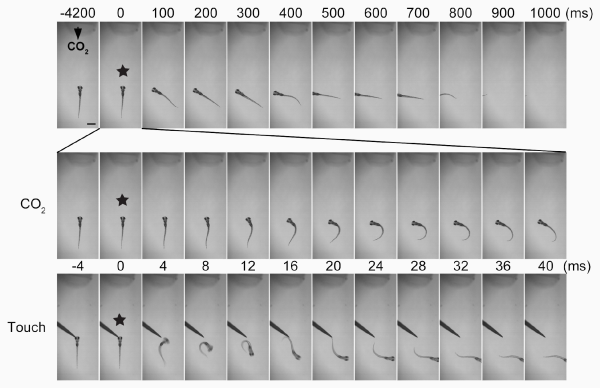

Larval zebrafish are known to have a fast response when touched on the head; they flee in a stereotyped pattern within 10 milliseconds. "In contrast," notes lead author Tetsuya Koide, "we showed that their avoidance response to carbon dioxide happened after around 4-5 seconds, which is about 400 to 500 times slower." Additionally, the escape routes taken by the fish to avoid carbon dioxide were much more variable than how they responded to being touched, and they swam away at much slower speeds. All these differences pointed to an as yet unknown sensation-response pathway in the brain.

When carbon dioxide is sensed by chemoreceptors in the zebrafish nose, a signal travels along the Terminal Nerve ➜ Trigeminal Ganglion ➜ Trigeminal Sensory Nucleus ➜ Reticulospinal Neurons pathway to trigger the slow avoidance response.

To identify the responsible pathway, the researchers used transgenic zebrafish made specially for calcium imaging. This technique visualizes brain activity by genetically expressing fluorescent protein sensitive to calcium, a key molecule involved in the transmission of neuronal signals. The team was able to see a series of responses to carbon dioxide in the brain, the earliest being in the olfactory bulb-the part of the brain that processes smell in mammals. A few seconds later, they saw responses in trigeminal sensory neurons-the nerve that carries touch and pain sensations from the face. The final response was from the habenula-a part of the brain known to be involved in learning associations with unpleasant experiences.

In order to determine which of these three systems was necessary for the response to carbon dioxide, the team used a laser to remove each one separately. They found that only damage to the trigeminal pathway and to the nose affected the response to carbon dioxide. This was somewhat surprising because damaging the olfactory pathway itself did not change the avoidance behavior. "This meant that a non-olfactory component in the nose is critical for avoiding carbon dioxide," explains Koide.

The team next wanted to determine how carbon dioxide was sensed in the nose. Calcium imaging of the zebrafish nose revealed a cluster of cells that responded to carbon dioxide. Tests indicated that these cells were part of the terminal nerve-also called cranial nerve zero-and their removal blocked the avoidance response to carbon dioxide. Thus, the zebrafish nose contains terminal nerve chemosensors that are unrelated to smell and that can control behavioral responses to noxious chemicals.

"We were surprised to find that the terminal nerve acts as a carbon dioxide sensor in zebrafish," says Koide. "Although it was identified as an additional cranial nerve in humans and other vertebrates more than a century ago, ours is the first to report its function in chemosensation." Indeed, the terminal nerve has been thought to function in reproductive behavior because it produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone, a major hormone which in turn stimulates the production of reproductive hormones.

"As humans and other vertebrates also possess the terminal nerve system," continues Koide, "we next hope to further characterize its chemosensory functions across different species, including humans."

Reference

- Tetsuya Koide, Yoichi Yabuki, Yoshihiro Yoshihara, "Terminal Nerve GnRH3 Neurons Mediate Slow Avoidance of Carbon Dioxide in Larval Zebrafish", Cell Reports, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.019

Contact

Laboratory Head

Yoshihiro Yoshihara

Laboratory for Neurobiology of Synapse

RIKEN Brain Science Institute

Adam Phillips

RIKEN International Affairs Division

Tel: +81-(0)48-462-1225 / Fax: +81-(0)48-463-3687

Email: pr@riken.jp

Avoidance response to carbon dioxide is slower than to touch

(top) the zebrafish avoidance response to carbon dioxide. (middle) A closer look at the first 40 ms after exposre to carbon dioxide. (bottom) the fast response to being touched. Note, when touched, the fish has already turned around and started to flee after 12 ms, and has moved away after 40 ms. In contrast, a fleeing the carbon dioxide takes about 5000 ms.

Zebrafish avoid carbon dioxide

Zebrafish do not avoid taurocholic acid (TCA)