Oct. 16, 2008 Research Highlight Biology

How the gut manages bacteria

A previously unknown mechanism enables the immune system in the gut to respond rapidly to changes in bacteria

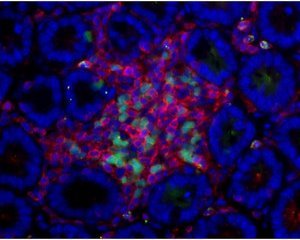

Figure 1: Adult LTi cells (green) interact with underlying stromal cells in the gut to recruit lymphocytes (red) in the small intestine. The nuclei of cells are stained in blue to reveal the gut structure.

Figure 1: Adult LTi cells (green) interact with underlying stromal cells in the gut to recruit lymphocytes (red) in the small intestine. The nuclei of cells are stained in blue to reveal the gut structure.

A RIKEN-led international research group has puzzled out details of the intricate mechanism by which the immune system in the gut can respond rapidly to changes in its bacterial environment. Eventually, the work could lead to better treatment and control of gut infections and inflammatory bowel diseases.

The gut is in direct contact with the external environment and houses at least 400 different species of bacteria in vast numbers. It maintains a finely tuned immune system built around immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies produced by B cells to protect the body against pathogens and manage the growth of benign organisms. Previous research by other researchers unraveled a mechanism whereby T cells control the formation of these IgA-producing B cells in organized multi-cellular structures called Peyer’s patches, which develop in the embryo. But such a system could take weeks to respond to invasive bacteria.

The latest work reveals a second mechanism that operates without intervention of T cells, and develops only after colonization of the intestine with bacteria, hence after birth. It involves another set of cellular structures called isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs).

In a recent paper in the journal Immunity 1, the researchers, led by Sidonia Fagarasan of the RIKEN Center for Allergy and Immunology in Yokohama, detail how these ILFs piece together, providing an understanding of the newly identified mechanism. They used strains of mice bred to lack compounds significant to the development of ILFs.

The researchers noticed that the numbers and size of ILFs in the gut paralleled the level of bacteria, increasing with bacterial colonization and decreasing with the use of antibiotics. Recently, they also discovered cells in adults similar to embryonic lymphoid tissue-inducer (LTi) cells essential to the development of immune centers, such as lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches.

Fagarasan and her colleagues showed that these adult LTi cells could interact with underlying stromal cells in the gut to recruit the cellular components of ILFs—B cells and antigen-presenting dendritic cells (Fig. 1). But the adult LTi cells only did this effectively in the presence of bacterial cells which stimulate an immune response, partly through the production of tumor necrosis factor. So ILFs are only formed when bacteria are present. The researchers also demonstrated that functioning ILFs could transform typical B cells that make immunoglobulin M into those that produce IgA.

“If we can understand more about these LTi cells and their interactions,” says Fagarasan, “it could provide us with the potential to manipulate the gut immune system.”

References

- 1. Tsuji, M., Suzuki, K., Kitamura, H., Maruya, M., Kinoshita, K., Ivanov, I.I., Itoh, K., Littman, D.R. & Fagarasan, S. Requirement for lymphoid tissue-inducer cells in isolated follicle formation and T cell-independent Immunoglobulin A generation in the gut. Immunity 29, 261–271 (2008). doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.014