Dec. 5, 2008 Research Highlight Biology

The need for new neurons

Tracking and halting the making of new neurons shows that continued neurogenesis is needed for spatial memory

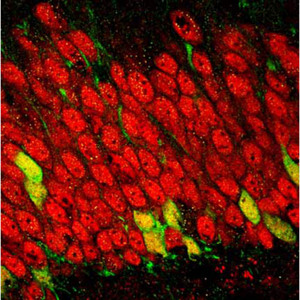

Figure 1: Recently generated neurons revealed by fluorescence (green/yellow signals) in the hippocampus of an adult mouse.

Figure 1: Recently generated neurons revealed by fluorescence (green/yellow signals) in the hippocampus of an adult mouse.

Recent work shows that persistent neurogenesis—the continuous production of new neurons—is needed for memory formation in adult mice. Neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb, the region of the brain responsible for smell perception, and in the hippocampus, the area of the brain required for memory formation, was first observed decades ago. However, whether newborn neurons generated by this process replace some or all older neurons in these regions was not known. Moreover, the biological importance of this incessant neurogenesis was not understood.

Now, a collaborative team led by Ryoichiro Kageyama of the Institute for Virus Research at Kyoto University and Shigeyoshi Itohara of the RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Wako, using complex genetic techniques to track the fate of and ablate the production of nascent neurons, has shown that persistent neurogenesis is needed for formation of spatial memories1.

To track the destination of newborn neurons, the researchers devised a genetic method to irreversibly and fluorescently ‘mark’ neural stem cells, which give rise to neurons. They observed that, with time, the proportion of fluorescent cells within the olfactory bulb gradually increased, and 12–18 months after the marking of neural stem cells, over 50% of olfactory bulb neurons were fluorescent. As the total number of neurons in the olfactory bulb remained constant, and the marking procedure did not kill off old neurons, the researchers concluded that newborn neurons gradually replace their aged counterparts in the olfactory bulb. In contrast, 12 months after neural stem cell marking, fluorescent neurons constituted only approximately 10% of neurons in the hippocampus (Fig. 1).

Next, the researchers genetically induced toxins in newborn neurons to halt neurogenesis. They found that the number of neurons in the olfactory bulb—which in normal situations remains constant—gradually decreased, whereas the number of neurons in the hippocampus—which typically grows with age—remained the same.

Surprisingly, halting neurogenesis had no detectable effect on short- or long-term memory of odors. However, as shown by a maze test, continued neurogenesis was required for spatial memory. Although the reason for this difference remains unclear, these findings ascribe biological importance to the previously mysterious observation of adult neurogenesis.

The neurogenesis-deficient mouse may provide a novel model animal for studies on Alzheimer’s disease and aging associated with dementia, according to Kageyama and Itohara. “And the genetic system for ablating a specific set of neurons is useful to test various hypotheses in neuroscience,” they say.

References

- 1. Imayoshi, I., Sakamoto, M., Ohtsuka, T., Takao, K., Miyakawa, T., Yamaguchi, M., Mori, K., Ikeda, T., Itohara, S. & Kageyama, R. Roles of continuous neurogenesis in the structural and functional integrity of the adult forebrain. Nature Neuroscience 11, 1153–1161 (2008). doi: 10.1038/nn.2185