Jun. 4, 2010 Research Highlight Biology

Evolutionary profits and losses

The disruption of melatonin production in laboratory mouse strains represents an apparent evolutionary advantage in terms of reproductive development

Animal models can yield valuable insights into the biology of human disorders, although they can also introduce additional levels of complexity that may make it a challenge to experimentally untangle the bases for specific phenotypes.

Tadafumi Kato and Takaoki Kasahara of the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Wako ran into such a challenge in their attempts to characterize abnormalities in the activity of melatonin, a hormone that fine-tunes the circadian rhythms that establish an organism’s day–night cycle, in their mouse model of bipolar disorder. “Since early times, researchers and psychiatrists have believed that melatonin has something to do with mood disorders, because many patients experience sleep disturbance and light therapy is used effectively in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder,” says Kasahara. However, they quickly found their efforts thwarted by the utter absence of melatonin from their laboratory mice.

Filling in the blanks

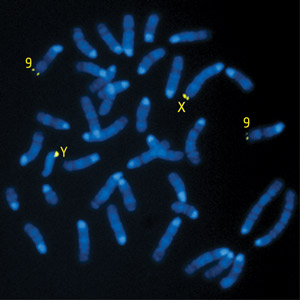

Figure 1: A fluorescent probe reveals the chromosomal location of the Hiomt gene. The gene itself is located in the pseudoautosomal region (PAR) of the two sex chromosomes (X and Y); a weak signal is also detected from a DNA stretch homologous to the PAR that resides within chromosome 9. © 2010 Takaoki Kasahara and Tadafumi Kato

Figure 1: A fluorescent probe reveals the chromosomal location of the Hiomt gene. The gene itself is located in the pseudoautosomal region (PAR) of the two sex chromosomes (X and Y); a weak signal is also detected from a DNA stretch homologous to the PAR that resides within chromosome 9. © 2010 Takaoki Kasahara and Tadafumi Kato

Indeed, a growing body of evidence suggests that several strains of laboratory mice—including the C57BL/6J (B6J) line used by Kato and Kasahara—are deficient in the production of melatonin, a process that depends on the sequential action of two enzymes: arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT) and hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase (HIOMT).

Scientists have successfully identified the mouse Aanatgene, and have even uncovered an inactivating mutation within this gene in B6J mice. However, even with high-quality mouse genome sequence data available, nobody has yet succeeded in tracking down its partner, Hiomt. “I studied the mechanism of circadian clocks when I was a PhD student, and I heard that mouse Hiomt was really enigmatic,” recalls Kasahara, “and even after being away from the field for about six years, I became aware that mouse Hiomt still had not been identified.”

This is no longer the case, thanks to an extensive analysis of the mouse genome by Kato, Kasahara and colleagues1. Using the rat HIOMT protein sequence as a basis for comparison they have finally managed to uncover this mysterious gene and have thereby revealed why it has remained hidden from scientists for so long.

Notably, mouse HIOMT bears only limited resemblance to its counterparts in other species, with an amino acid sequence that is less than 70% identical to that of the rat protein. Furthermore, this gene was likely masked by its residence within the pseudoautosomal region (PAR), a poorly characterized stretch of DNA within the sex chromosomes that enables them to efficiently ‘pair up’ and undergo recombination during meiosis (Fig. 1). “The PAR contains extremely repetitive sequences and high guanine-cytosine content, both of which make it difficult to sequence using either traditional or next-generation sequencing methods,” says Kasahara.

Developmental consequences

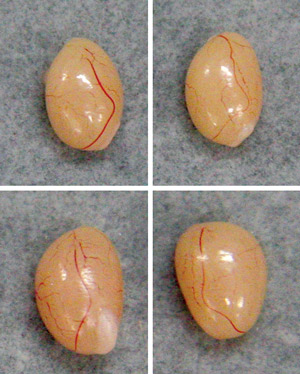

Figure 2: Melatonin productivity has a marked effect on male reproductive development in mice. Relative to specimens collected from mice that produce melatonin (top), those collected from melatonin-deficient males with the B6J version of the Hiomt gene (bottom)) show significantly accelerated testicular growth by eight weeks of age. © 2010 Takaoki Kasahara and Tadafumi Kato

Figure 2: Melatonin productivity has a marked effect on male reproductive development in mice. Relative to specimens collected from mice that produce melatonin (top), those collected from melatonin-deficient males with the B6J version of the Hiomt gene (bottom)) show significantly accelerated testicular growth by eight weeks of age. © 2010 Takaoki Kasahara and Tadafumi Kato

Closer analysis of the sequence of this gene revealed two notable sequence variations in B6J mice relative to MSM animals—a strain derived more recently from wild mice that exhibits normal melatonin production. Both of these changes affect the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein, and the investigators showed that each mutation leads to a strong reduction in HIOMT levels. These mutations also proved to be widespread among a variety of other inbred mouse strains, including several lines commonly employed in laboratory research.

Kato, Kasahara and colleagues also noted that although this HIOMT deficiency appears to have a limited impact on circadian behaviors, it has a clear effect on gonadal development; melatonin-deficient animals with the B6J versions of the Hiomt and/or Aanat genes exhibited significantly greater testicular growth than their melatonin-producing counterparts (Fig. 2). Conversely, in experiments with ICR mice, another melatonin-deficient strain, the researchers showed that treatment with melatonin was associated with a reduction in testicular weight.

These findings are in keeping with other data showing a vital link between melatonin and reproductive development—including observations in human patients. “Children with little or no melatonin due to pineal tumors often show premature sexual maturation,” says Kasahara.

Evolution in a cage

Because these defects appear to be specifically prevalent among cultivated strains of laboratory mice, it appears likely that there is some manner of selection taking place that favors the emergence of strains with reduced melatonin levels and accelerated reproductive development—even if this evolution was unintentional and, until now, invisible. This finding is supported by similar research in domesticated chickens, which has spotlighted the emergence of other gene variations that may potentially influence the same developmental pathway2. “One of the most intriguing [variants] is found in the gene encoding the receptor for thyroid-stimulating hormone, because TSH and melatonin are closely related in seasonal breeding,” says Kasahara.

These findings could also have potential implications for previous animal studies that have investigated circadian rhythms, given that much of this research has been conducted in B6J and other inbred strains. For example, one recent study has shown that the circadian rhythm defects observed in the widely used B6J-derived Clock mutant mice are markedly diminished in the presence of normal levels of melatonin3.

These findings will closely inform future work from Kasahara and Kato, who are in the process of engineering a melatonin-producing B6J strain for use in their future investigations of mood disorders. However, Kasahara also suggests that conventional laboratory strains in general may be too interbred for their own good. “Our B6J mouse model for mood disorder has many phenotypes similar to bipolar disorder, but they don’t get manic spontaneously,” he says. “I hypothesize that laboratory mice have lost their potential to develop manic or aggressive episodes, and we are consequently using wild-derived mice, which are very aggressive, alert and agile in order to study these disorders.”

References

- 1. Kasahara, T., Abe, K., Mekada, K., Yoshiki, A. & Kato, T. Genetic variation of melatonin productivity in laboratory mice under domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 107, 6412–6417 (2010). doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914399107

- 2. Rubin, C.-J., Zody, M.C., Eriksson, J., Meadows, J.R.S., Sherwood, E., Webster, M.T., et al. Whole-genome resequencing reveals loci under selection during chicken domestication. Nature 464, 587-91 (2010). doi: 10.1038/nature08832

- 3. Shimomura, K., Lowrey, P.L., Vitaterna, M.H., Buhr, E.D., Kumar, V., Hanna, P., Omura, C., Izumo, M., Low, S.S., Barrett, R.K. et al. Genetic suppression of the circadian Clock mutation by the melatonin biosynthesis pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA published online, 19 April 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004368107

About the Researcher

Takaoki Kasahara

Takaoki Kasahara was born in Fukui, Japan, in 1972. He graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences, The University of Tokyo, in 1996. He studied the molecular mechanism underlying the phase shifting of circadian rhythms by light when he was a PhD student. After he obtained his PhD in 2001 from the University of Tokyo, he joined the Laboratory for Molecular Dynamics of Mental Disorders, RIKEN Brain Science Institute. He has been studying the pathophysiology of mood disorders and developing mouse models for these disorders. His mouse model for bipolar disorder was reviewed in the premier issue of RIKEN RESEARCH 1, 10 (2006). He was a Special Postdoctoral Researcher (RIKEN) from 2003 to 2006 and is now a Deputy Team Leader.