Apr. 1, 2011 Research Highlight Biology

Supporting the troops

In the absence of vitamin A, the body loses immune cells that put the brakes on the earliest stages of infection

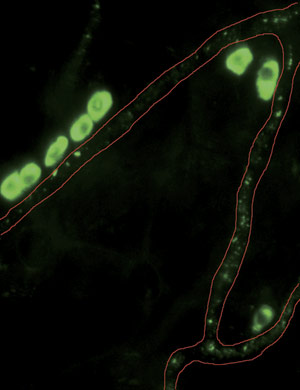

Figure 1: Once activated by the presence of pathogens, B1 cells develop into IgM-secreting cells (green) which travel along the blood vessels (outlined in red) from the peritoneal cavity into the effector sites such as spleen. © 2011 Sidonia Fagarasan

Figure 1: Once activated by the presence of pathogens, B1 cells develop into IgM-secreting cells (green) which travel along the blood vessels (outlined in red) from the peritoneal cavity into the effector sites such as spleen. © 2011 Sidonia Fagarasan

Scientists have recognized the immune-boosting capabilities of vitamin A for the better part of a century, even without fully understanding how it helps the body fight off bacteria and viruses. “Soon after its discovery, vitamin A was termed ‘the anti-infective vitamin’ and was widely used to enhance recovery; but with the introduction of antibiotics, the therapeutic use of vitamin A diminished,” says Sidonia Fagarasan of the RIKEN Research Center for Allergy and Immunology in Yokohama.

Fagarasan and her colleagues have now revealed how vitamin A deficiency can critically undermine the body’s initial defense against infection1. B1 cells within the peritoneal cavity (PEC), the space surrounding the intestines and other organs, are important ‘first responders’ to the presence of pathogens (Fig. 1). Upon activation, B1 cells mature into cells that produce immunoglobulin M (IgM) and A (IgA) antibodies that target bacteria and viruses in the bloodstream and gut, respectively. “These cells usually act at the early time window after infection, thus preventing the expansion of microorganisms,” explains Fagarasan.

Mikako Maruya, a young researcher with her team, observed dramatic depletion of PEC B1 cells in mice fed a vitamin A-free diet, which grew more severe with age. Accordingly, these vitamin A-deficient (VAD) animals also produced lower levels of both IgA and IgM, and failed to marshal an effective antibody response following injection with pneumonia vaccine. B1 cells transplanted from healthy donors to VAD animals showed impaired proliferation, and considerably dwindled in number over the course of a week. Importantly, bone marrow-derived stem cells from VAD mice retained the capacity to give rise to B1 cells, although they failed to do so in the absence of vitamin A.

The key turned out to be nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFATc1), a transcription factor protein that regulates expression of numerous important genes in B1 cells. The researchers observed reduced NFATc1 levels in VAD B1 cells, but found that expression could be largely restored if these mice were injected with ATRA, a product of cellular vitamin A metabolism. This also led to rapid B1 cell proliferation, which increased in number by more than four-fold increase within 10 days of injection.

Motivated by these findings, Fagarasan is now exploring how levels of vitamin A affect other components of the immune response to infection. “We were very excited to discover something that we had never thought about, that active products of vitamin A contribute to the induction of some very important transcription factors,” she says.

References

- 1. Maruya, M., Suzuki, K., Fujimoto, H., Miyajima, M., Kanagawa, O., Wakayama, T. & Fagarasan, S. Vitamin A-dependent transcriptional activation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 (NFATc1) is critical for the development and survival of B1 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 108, 722–727 (2011). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014697108