Nov. 11, 2011 Research Highlight Biology

Inheriting stress

Flies can pass the effects of stress to their young in the form of chromosomal modifications that alter expression of selected genes

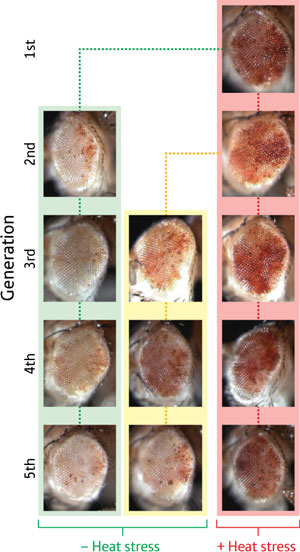

Figure 1: When wm4 flies are exposed to heat stress, they display increased white expression, resulting in red eye pigmentation (right column). Offspring of these flies retain this effect (green line); if these 2nd generation flies are also heat-stressed (yellow line), the effects are still visible in their 5th generation offspring. © 2011 Ki-Hyeon Seong

Figure 1: When wm4 flies are exposed to heat stress, they display increased white expression, resulting in red eye pigmentation (right column). Offspring of these flies retain this effect (green line); if these 2nd generation flies are also heat-stressed (yellow line), the effects are still visible in their 5th generation offspring. © 2011 Ki-Hyeon Seong

Most people don’t realize the extent of the biochemical and physiological changes that stress causes; indeed, new research suggests that offspring might even be vulnerable to changes in gene expression wrought by chronic parental stress1.

Different external traumas all appear to trigger a common response pathway, which is mediated in part by the activation transcription factor-2 (ATF-2) protein. “Environmental stress, psychological stresses, infection stress and nutrition stress can all activate ATF-2,” explains Shunsuke Ishii, a scientist at the RIKEN Advanced Science Institute in Tsukuba, whose group first cloned ATF-2 nearly two decades ago.

Ishii was inspired by studies in yeast suggesting that ATF-2 triggers chemical changes to chromatin, the material formed when chromosomal DNA wraps around histone proteins. These changes can markedly affect gene expression, a mechanism known as ‘epigenetic regulation’. In their recently published study, Ishii and his colleagues examined whether or not ATF-2 is associated with epigenetic regulation in the fruit flyDrosophila melanogaster.

The strain of D. melonogaster known as wm4 features a genomic rearrangement that results in epigenetic silencing of the white gene, a locus that controls eye color; and the researchers used this strain as their primary experimental model. They determined that ATF-2 normally binds to the chromatin and contributes to white silencing in these flies. However, when the flies were exposed to stress from heat or a high-salt diet, ATF-2 was released from the chromatin, which subsequently underwent chemical modifications that led to increased white expression.

Since epigenetic changes can be transmitted across generations, Ishii and colleagues performed a series of experiments in which heat-stressed flies were crossed with unstressed counterparts. Remarkably, offspring from these crosses maintained the increased white expression seen in the stressed parent. When these offspring were in turn subjected to heat stress and then crossed with unstressed flies, the effects were transmitted as far as the fifth generation (Fig. 1). “This shows that the effects of stress can be inherited without DNA sequence change,” says Ishii.

All of these effects were dependent on ATF-2. The researchers also identified dozens of genes whose activity may be potentially modulated by this factor during stress response. Ishii hopes to further explore the biological significance of this finding in future studies. “We are planning to identify such target genes of ATF-2 and prove the inheritance of their stress-induced expression change,” he says. “This could be correlated with various diseases.”

References

- 1. Seong, K.-H., Dong, L., Shimizu, H., Nakamura, R. & Ishii, S. Inheritance of stress-induced, ATF-2-dependent epigenetic change. Cell 145, 1049–1061 (2011). doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.029