Nov. 8, 2013 Research Highlight Biology

In search of a sugar’s secrets

The discovery of the origin of enigmatic ‘waste’ sugar molecules within the cell also hints that they serve some as-yet-undefined function

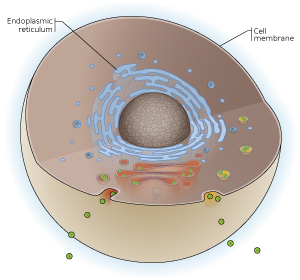

Figure 1: In the endoplasmic reticulum, N-glycosylation of proteins results in the formation of free oligosaccharides. © 2013 RIKEN–Max Planck Joint Research Center

Figure 1: In the endoplasmic reticulum, N-glycosylation of proteins results in the formation of free oligosaccharides. © 2013 RIKEN–Max Planck Joint Research Center

Within a cellular compartment called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), certain proteins become decorated with sugar molecules by a process called N-glycosylation, before being delivered to the cell surface. This process also gives rise to a population of untethered sugar molecules known as free oligosaccharides (fOSs). Tadashi Suzuki, Yoichiro Harada and colleagues from the RIKEN–Max Planck Joint Research Center for Systems Chemical Biology have now determined how fOSs are produced and at the same time have uncovered some important new questions1.

The oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) enzyme complex facilitates N-glycosylation by transferring preassembled sugar structures from dolichyl pyrophosphoryl-linked oligosaccharide (DLO) molecules onto the target protein. Scientists had long believed that fOSs result from the breakdown of DLOs until Suzuki discovered an enzyme in the cytoplasm called peptide:N-glycanase (PNGase) that can generate fOSs by acting on improperly folded glycosylated proteins. While initially skeptical, the scientific community eventually embraced this as the primary mechanism for fOS production. Suzuki, however, suspected that the biological picture was even more complicated, particularly since yeast cells lacking PNGase still produce low levels of fOSs.

To clarify the situation, he and Harada set out in search of this yet-undiscovered source of fOSs. First, they verified that PNGase-deficient yeast cells produce fOSs within the ER, which are subsequently exported to and degraded in the cytosol. Prior studies suggested that OST—the same enzyme that drives N-glycosylation—can also break down DLOs to yield fOSs. After obtaining initial data to support this hypothesis from experiments with mutant yeast strains, Harada went through the laborious process of isolating the intact, eight-protein OST complex. Experiments with purified OST showed that the enzyme can indeed convert DLO molecules into fOSs, providing new support for the DLO-centered model of fOS production.

Importantly, the research revealed that a sharp increase in the concentration of available DLOs does not lead to an equivalent bump in fOS production, suggesting that this is not an accidental process. “Our data suggest that OST-mediated fOS release is a highly regulated reaction,” says Suzuki. Given that mammalian cells appear to produce the majority of their fOSs through a similar non-PNGase mechanism, Suzuki hypothesizes that this pathway may serve some specific function in higher eukaryotes, which his team hopes to uncover in future studies. “It looks like a waste if fOSs are merely the junk produced by erroneous activity of OST,” he says. “We believe there must be a reason for cells to engage in such an apparent waste of energy.”

References

- 1. Harada, Y., Buser, R., Ngwa, E. M., Hirayama, H., Aebi, M. & Suzuki, T. Eukaryotic oligosaccharyltransferase generates free oligosaccharides during N-glycosylation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry advance online publication, 23 September 2013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.486985