Aug. 1, 2014 Research Highlight Physics / Astronomy

Probing the proton

A two-stage trap for single protons leads to measurement of their magnetic properties with unprecedented precision

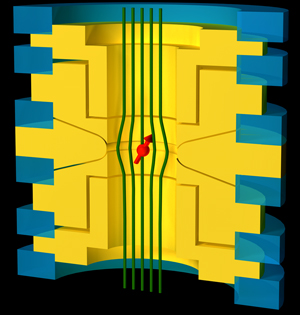

Figure 1: In a Penning trap, the magnetic moment of a proton (red arrow) precesses with respect to the magnetic field (green). © 2014 Stefan Ulmer, RIKEN Ulmer Initiative Research Unit

Figure 1: In a Penning trap, the magnetic moment of a proton (red arrow) precesses with respect to the magnetic field (green). © 2014 Stefan Ulmer, RIKEN Ulmer Initiative Research Unit

Detailed knowledge of the physical properties of the building blocks of matter is fundamental to our understanding of the Universe. These building blocks include the protons, neutrons and electrons that make up an atom, and physicists continue to strive to measure the mass, size, electric charge and magnetic properties of these subatomic particles with ever-greater precision in order to advance our understanding of the physical world.

As part of a collaboration between RIKEN and several research centers based in Germany, including the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics at Heidelberg and GSI in Darmstadt, Stefan Ulmer and colleagues from the RIKEN Ulmer Initiative Research Unit have now performed the most precise measurement of the magnetic moment of a proton to date1.

The magnetic moment of a proton defines its response to a magnetic field. The previous record for the most precise measurement of this property has stood for over 40 years. In 1972, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States investigated the microwaves emitted by hydrogen atoms under the influence of strong magnetic fields. Their experimental results, combined with theoretical corrections, made it possible to calculate the magnetic moment of the proton to an accuracy of close to ten parts in a billion.

In an attempt to surpass this record, Ulmer and his colleagues directly measured the magnetic moment of the proton using a Penning-trap technique. This approach allows individual protons to be trapped using an electric field, which creates an electrostatic well that confines the particle in one direction, while a strong magnetic field prevents it from escaping in the other direction. A single trapped proton oscillates at a characteristic frequency due to rotation, or ‘precession’, of the magnetic moment about an axis parallel to the magnetic field of the trap (Fig. 1). The time required to complete a single oscillation is defined by the particle’s magnetic moment, mass and charge, and also the strength of the magnetic field. Measuring the frequency of the oscillation, called the cyclotron frequency, and the precession, known as the Larmor frequency, provides information about the particle’s fundamental properties.

One trap or two

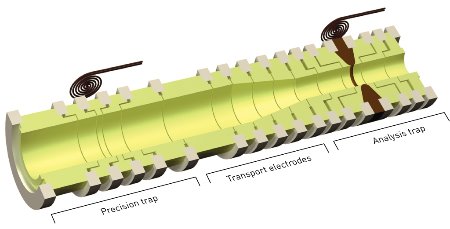

Figure 2: The double Penning trap separates the spin state analysis from the precision frequency measurements to give a more accurate value of the magnetic moment of a proton. Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. 1 © 2014 A. Mooser et al.

Figure 2: The double Penning trap separates the spin state analysis from the precision frequency measurements to give a more accurate value of the magnetic moment of a proton. Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. 1 © 2014 A. Mooser et al.

In Penning-trap experiments, free protons are first produced by bombarding a polyethylene target with a beam of electrons and then isolated in the trap. When sealed in an ultra-low-pressure vacuum chamber and cooled to just four degrees above absolute zero, the trap can hold a single proton for more than a year—the timeframe necessary to obtain the desired measurement precision.

Scientists have previously used Penning traps to measure the magnetic moment of electrons and have achieved a precision of 3.8 parts in a trillion. The magnetic moment of a proton, however, is about 658 times smaller than that of an electron, which requires a far more sensitive experimental setup.

In the Penning trap, an aberration or ‘inhomogeneity’ in the longitudinal magnetic field is applied in order to couple the particle’s magnetic moment—associated with its ‘spin’—to its axial oscillation frequency. By measuring the resultant frequency, researchers can nondestructively detect the particle’s spin state, and by taking measurements while alternately driving spin transitions with a well-characterized radiofrequency drive, they can identify the Larmor frequency. The problem with this approach, however, is that the magnetic inhomogeneity needed to make the spin-flips observable—which for protons is 2,000 times stronger than for electrons—makes it difficult to measure the oscillation frequency precisely. In fact, previous attempts to measure the proton magnetic moment using such a Penning-trap technique have resulted in poor precision of just several parts per million—far less precise than the indirect hydrogen-spectroscopy method used in 1972.

To overcome this problem, the collaborative research team built a double Penning trap (Fig. 2) consisting of an ‘analysis’ trap containing the magnetic inhomogeneity, and a second ‘precision’ trap located over four centimeters away so as to attenuate the interfering effect of the inhomogeneity. The team then fitted electrodes to shuttle the single proton between the two traps as desired. “The particle’s spin state could be identified in the analysis trap, and then the particle would be shuttled to the precision trap where the cyclotron frequency could be measured and where spin-flips were driven,” explains Ulmer.

A test of precision

Using the double Penning trap, Ulmer and his colleagues cycled an individual proton between the two traps several hundred times. This allowed them to measure the magnetic moment of the proton with a precision 760 times better than the 1972 result. The value of the magnetic moment they obtained was 2.792847350 times the nuclear magneton, which is a physical constant for the magnetic moment known precisely in terms of other well-defined fundamental constants. This value is in excellent agreement with the currently accepted value, known as the CODATA value, but with a higher precision of 3.3 parts per billion.

Such high-precision experiments are only valid, however, when coupled with a detailed analysis of the various sources of statistical and systematic error. These errors include the effect of the small magnetic-field inhomogeneity in the precision trap, asymmetry in the electrostatic well or the magnetic fields, as well as relativistic effects. The researchers believe that they can improve the accuracy of their measurement by a factor of ten by reducing the residual field inhomogeneity in the precision trap and by employing phase-sensitive measuring techniques. “We will next apply this technique to measuring the magnetic moment of the antiproton,” says Ulmer. “This will provide a sensitive test of matter–antimatter symmetry.”

References

- 1. Mooser, A., Ulmer, S., Blaum, K., Franke, K., Kracke, H., Leiteritz, C., Quint, W., Rodegheri, C. C., Smorra, C. & Walz, J. Direct high-precision measurement of the magnetic moment of the proton. Nature 509, 596–599 (2014). doi: 10.1038/nature13388

About the Researcher

Stefan Ulmer (right) and Andreas Mooser

Stefan Ulmer received his PhD in 2011 from Heidelberg University, for which he made the first observation of spin-flips with a single trapped proton. He later joined a team at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) as a postdoctoral fellow and contributed to the production of the first beam of antihydrogen atoms. He currently leads the RIKEN Ulmer Initiative Research Unit, and in June 2013 became the spokesperson for the Baryon Antibaryon Symmetry Experiment (BASE) collaboration at CERN, which aims to measure the magnetic moment of the antiproton with high precision. Ulmer received the 2014 IUPAP Young Scientist (Early Career) Prize in Fundamental Metrology for his efforts to measure the magnetic moments of the proton and antiproton.

Andreas Mooser studied physics at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) in Germany and the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. He obtained his PhD from JGU in 2014, focusing his research on the first observation of single spin-flips of a single proton and measurement of the magnetic moment of the proton with high precision. Mooser recently joined the RIKEN Ulmer Initiative Research Unit as a postdoctoral fellow and is contributing to BASE to conduct experiments that stringently test CPT (charge, parity and time reversal) invariance.