Jun. 2, 2017 Research Highlight Chemistry

Lasers pick up good vibrations

The changes to the structure of a light-sensing protein have been tracked over incredibly short time scales

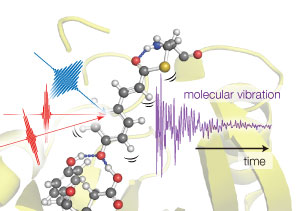

Figure 1: Tahei Tahara and his team used three light pulses to excite vibrations in photoactive yellow protein molecules. By monitoring how the vibrations varied over the first few hundreds of femtoseconds, the team could determine how protein’s structure changed over this time. © 2017 RIKEN Molecular Spectroscopy Laboratory

Figure 1: Tahei Tahara and his team used three light pulses to excite vibrations in photoactive yellow protein molecules. By monitoring how the vibrations varied over the first few hundreds of femtoseconds, the team could determine how protein’s structure changed over this time. © 2017 RIKEN Molecular Spectroscopy Laboratory

Using an ultrafast spectroscopic technique, RIKEN researchers have observed a light-sensitive protein in the first few quadrillionths of a second after it absorbs a photon of light. This information will provide scientists with valuable clues about how such light-sensitive proteins achieve high signal transduction efficiencies.

Light-sensitive proteins form a key part of the sensory systems by which organisms detect light around them. For example, the aquatic light-harvesting bacterium Halorhodospira halophila detects blue light using the photoactive yellow protein (PYP). The organism swims away from blue wavelengths—a response thought to avoid exposure to harmful blue light.

Previous studies had shown that blue light triggers a structural twist known as trans -to- cis isomerization at the light-capturing heart of PYP. But this photon-triggered rearrangement of the protein occurs so rapidly that it has proved difficult to observe, generating contradictory results.

Since previous studies using x-rays and infrared spectroscopy did not provide consistent structural details, Tahei Tahara from the RIKEN Molecular Spectroscopy Laboratory and co-workers adopted a different approach. They used Raman spectroscopy, which is similar to infrared spectroscopy in that it uses laser pulses to probe the molecular vibrations of compounds, but employs visible light rather than longer wavelength infrared radiation.

The team used a Raman technique that they had developed called time-resolved impulsive stimulated Raman spectroscopy (TR-ISRS). “I believe TR-ISRS is one of the ultimate forms of Raman spectroscopy,” Tahara says.

Using three precisely timed light pulses, the team could trigger photon uptake in the PYP molecules in a sample, synchronize their motion, and then monitor any changes in the protein’s structure over the next few hundreds of femtoseconds (Fig. 1; one femtosecond is 10−15 second).

Most of PYP’s vibrational signals remained steady over this time frame, showing that the protein does not flip from the trans to the cis conformational state until later in the process. But one vibrational signal dropped rapidly in intensity following photon absorption. The team showed this change relates to the rapid weakening of a hydrogen bond that normally anchors the protein’s light-capturing portion, allowing PYP to flex during the subsequent isomerization.

“TR-ISRS is a very versatile vibrational spectroscopic method, having extremely high time resolution and sensitivity,” Tahara says. “We would like to apply it to a wide range of problems, from studying fundamental molecules to understanding the mechanism of newly found photoresponsive proteins, as well as new materials. We have already started research in this direction,” he adds.

Related contents

References

- 1. Kuramochi, H., Takeuchi, S., Yonezawa, K., Kamikubo, H., Kataoka, M. & Tahara, T. Probing the early stages of photoreception in photoactive yellow protein with ultrafast time-domain Raman spectroscopy. Nature Chemistry advanced online publication, February 2017 doi: 10.1038/nchem.2717