Jun. 26, 2020 Feature Highlight Medicine / Disease Computing / Math

Friendly bacteria fight stomach ulcers

A family of bacteria in the stomachs of mice activate immune reactions that may help combat the negative effects of Helicobacter pylori, which causes most human gastric ulcers.

A group from the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences has shown how a family of bacteria stimulates the stomach’s immune system to produce a protective antibody coating. This coating is thought to ameliorate the impact of pathogens, such as the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which is linked to most gastric ulcers and also potentially to stomach cancer. Revealing a similar mechanism in humans could lead to new probiotics to treat, or prevent, stomach ulcers and cancers.

A friendly bacteria found

© nobeastsofierce/ Getty Images

© nobeastsofierce/ Getty Images

To understand how the stomach typically manages H. pylori infections and other pathogens, the RIKEN team, led by Naoko Satoh-Takayama, wanted to understand which immune cells were at play.

The human immune system has three broad groups of immune cells. The main two are linked to innate and adaptive immunity. Innate immune cells respond rapidly to pathogens, but lack specificity—a kind of first-line-of-defense, shotgun approach. In contrast, adaptive immune cells take longer to respond, but are much more targeted in their attack on harmful bacteria and viruses. The latter’s B- and T-cells are more like guided missiles.

In between these two groups (in terms of function) are innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). Like innate immune cells, ILCs respond quickly and lack the receptors for antigens that give adaptive immunity cells their specificity. But like T-cells, they emit a cocktail of proteins that prime the immune system for a more specific response. Satoh-Takayama was part of the team that discovered these cells while working at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. That group became the first to publish on ILCs in 2008 when they discovered ILC3, one of the three known types.

To better understand stomach ILCs, Satoh-Takayama and her RIKEN co-workers started checking for ILC3 populations in the stomachs of mice. These ILCs are abundant in mice intestines, and so the group assumed it would be the same in the stomach. “But we found nothing at all—no ILC3s!” Satoh-Takayama says. “My initial reaction was: Where do we go from here?” The group then checked ILC1s and ILC2s, and found that of the three ILCs, ILC2s were most plentiful in the stomachs of mice.

ILC2s were then found to be rapidly produced in the stomach in response to H. pylori infection. By tracing the interactions back from these cells, the team found that the S24-7 bacteria family (commonly found in human and mouse stomachs) were also associated with an increase of ILC2s. They then showed that S24-7 bacteria stimulate production of two proteins that cells use to communicate—interleukins 7 and 33—and, in turn, these trigger the propagation and activation of ILC2s. ILC2-derived IL-5 then results in the production of the blood protein antibody immunoglobulin A, which coats stomach microbes, effectively controlling potentially harmful bacteria.

A probiotic for ulcers?

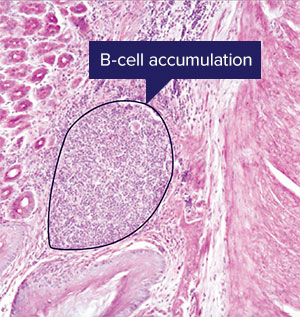

The proliferation of B-cells seen here after two weeks of infection by Helicobacter pylori is a slower adaptive immune response. A RIKEN team's insights into the role of the S24-7 bacteria family in supporting a slightly faster response from innate lymphoid cells may lead to a probiotic to treat stomach infections © RIKEN

The proliferation of B-cells seen here after two weeks of infection by Helicobacter pylori is a slower adaptive immune response. A RIKEN team's insights into the role of the S24-7 bacteria family in supporting a slightly faster response from innate lymphoid cells may lead to a probiotic to treat stomach infections © RIKEN

Many studies have looked at how microbes in the large and small intestines interact with the immune system, but because of its acidic nature, the stomach—one of the first port of calls for food entering our digestive system—has been largely ignored until recently, says Satoh-Takayama. “That’s because it was thought unlikely that bacteria could endure the highly acidic conditions of the stomach,” she explains.

But since H. pylori bacteria were found in the stomach and linked to ulcers in the 1980s (a discovery that earned Barry Marshall and Robin Warren the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2005), stomach bacteria have come increasingly into the spotlight.

The right balance of bacteria across the whole digestive system has also recently been linked to many beneficial effects, such as helping the immune system fight pathogens and break down food, and providing protection against diabetes, obesity, colon cancer and depression. As a result, some companies already make probiotics, doses of beneficial bacteria, that they claim better regulate the bacterial balance in the digestive system to then boost the immune system.

Most reliably, several combined analyses of dozens of studies have concluded that probiotics may help prevent some of the common side effects of antibiotics. Antibiotics disrupt communities of beneficial bacteria in the gut and these emptied niches are sometimes filled by harmful bacteria that secrete toxins, causing inflammation and diarrhea. Adding yogurt or other probiotics to a diet during and after a course of antibiotics seems to decrease the chances of subsequently developing opportunistic infections in the intestine.

Could something similar be true for H. pylori? H. pylori infections are found in about 60% of adult stomachs across the world, but only about 10% will develop a stomach ulcer. Generally, this happens if a treatment of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs damages the stomach lining and an H. pylori infection gets out of hand and causes an ulcer at the site. If that’s the case, could a dose of specific beneficial stomach bacteria have a protective effect when taking anti-inflammatory drugs?

Moreover, if an H. pylori strain proves to be one of a growing number of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (sometimes known as superbugs), taking S24-7 inducible bacteria as a probiotic could provide one possible alternative treatment, Satoh-Takayama says.

But before these possibilities can be addressed, researchers need to understand how much the recent findings carry over to humans—something that Satoh-Takayama and her team are keen to investigate. “Unfortunately, the function of IL-5 is a little bit different in mice. But there is another, similar mechanism with IL-13, for example,” she says. “We’re trying to find medical researchers to collaborate with so that we can further investigate this link between gut microbes and immune cells in humans.”

Reference

- 1. Satoh-Takayama, N., Kato, T., Motomura, Y., Kageyama, T., Taguchi-Atarashi, N., Kinoshita-Daitoku, R., Kuroda, E., Di Santo, J. P., Mimuro, H., Moro, K. et al. Bacteria-induced group 2 innate lymphoid cells in the stomach provide immune protection through induction of IgA. Immunity 52, 635−649 (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.002

About the researcher

Naoko Satoh-Takayama received her PhD from the University of Tokyo in 2007 under the direction of Hiroshi Kiyono. After graduating, she joined James Di Santo’s group in the Institut Pasteur, France, on a scholarship. In 2008, she identified and reported a novel cell subset of innate lymphoid cells, a world first, and became an assistant professor at the Institute Pasteur in 2010. She moved to RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences in 2015 and joined Hiroshi Ohno’s lab. She is currently investigating the importance of commensal and pathogenic bacteria in the function of innate lymphoid cells as a senior research scientist.