Aug. 15, 2024 Perspectives Other

More than 100 years of collaboration

Two leading research institutes located far from each other, but formed in the early 20th century along similar lines, continue to make breakthroughs together.

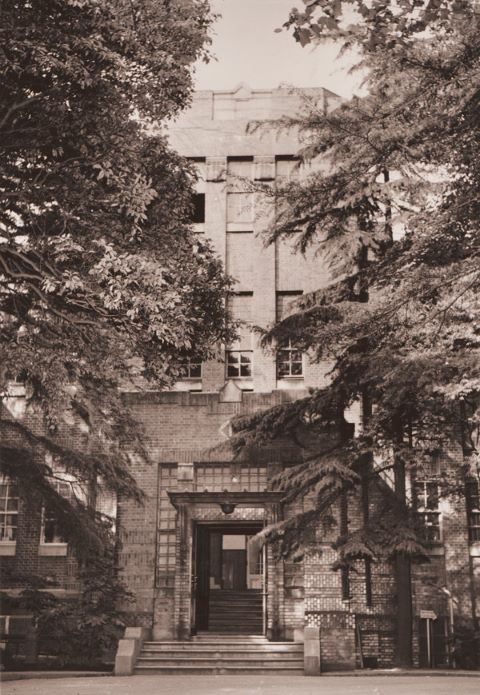

Chemist Setsuro Tamaru helped design RIKEN's first building, the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, which was based on what is now known as the MPG Fritz Haber Institute. © 2024 RIKEN

On April 9, 2024, a ceremony was held at the German embassy in Tokyo to celebrate 40 years of formal research collaboration and a much longer special relationship between RIKEN and the Max Planck Institute.

Historically, the Max Planck Society (MPG), Germany’s premier cluster of research institutes, was a prominent model for the founders of RIKEN. MPG, which was then known as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, was founded in 1911, six years before RIKEN.

In many countries, there was a perception among the academics and politicians that the rapid pace of industrialization had demonstrated that many new technical problems could only be solved with greater knowledge of chemical or physical principles. The scientific communities in both Germany and Japan felt institutions dedicated to basic research would be needed to make that possible.

Max Plank came about as an attempt to create a system of specialized, independent, non-governmental research institutes that would exist alongside universities, a move that has molded the modern-day research environment within Germany.

RIKEN, for its part, was founded when a similar idea was put forward by a number of prominent scientists, including chemist Jokichi Takamine—who was the first to isolate the human hormone adrenaline in a way that could be used for medicine. Today, adrenaline is used to treat heart and respiratory problems, and severe allergic reactions.

Takamine, who was already involved in successful collaborations with overseas scientists, argued that Japan needed its own national scientific research center, in line with its international standing and to help other Japanese academics develop similar collaborations.

When RIKEN was founded in 1917, it was conceived as a specialized institute. Its model was similar in form to the Kaiser Wilhelm Society—which in turn echoed the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (1901) and the Carnegie Institution for Science (1902) in the United States, and the Institut Pasteur (1887) in France. But RIKEN’s relationship with the Kaiser Wilhelm Society was special.

Even RIKEN’s first building, erected in the Komagome area of Tokyo, was based on what is now known as the MPG Fritz Haber Institute. The building was conceived by chemist Setsuro Tamaru, who became one of RIKEN’s first chief scientists.

Tamaru based the design on the imposing Kaiser Wilhelm Society structure where he had worked in the years prior with Frizt Haber, whose work on the Haber-Bosch process of ammonia synthesis would win him a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918.

Modern models

This year marks the 40th anniversary of a more formalized relationship between MPG and RIKEN that began in 1984, RIKEN and MPG signed their first official research cooperation agreement.

From this agreement has sprung many prominent research initiatives. In 2011 the Max Planck-RIKEN Center for Systems Chemical Biology formed as a collaboration between the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology, the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces and the RIKEN Advanced Science Institute.

While the joint center wound up in 2022, the partnership was a fruitful one. For example, one group—led by Peter Seeberger of the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces and Naoyuki Taniguchi, formerly of the Systems Glycobiology Research Group at RIKEN—identified a new drug target for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

They showed that the removal of the GnT-III gene in mice resulted in a marked decrease in the formation of amyloid-beta peptide plaques, leading to an improvement in cognitive function. Many groups globally are now working on targeting the expression of this gene to treat Alzheimer’s disease.

In 2019, another joint center was established between RIKEN and partners at the Max Planck Institute for nuclear physics, the Max Planck Institute for quantum optics, and the National Metrology Institute of Germany (PTB).

Together the parent institutes involved have funded the MPG-PTB-RIKEN Center for Time, Constants, and Fundamental Symmetries to the tune of US$9.5 million (¥1,489 million) over five years.

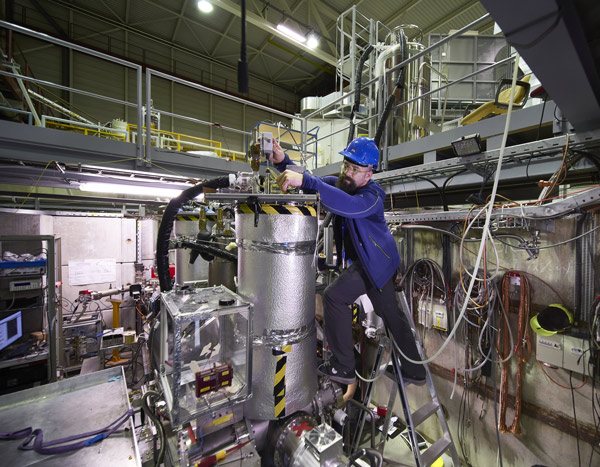

The center is dedicated to developing incredibly sensitive instruments—and RIKEN-led sub-projects have ranged from developing clocks that are more precise than the world’s most accurate timepieces, to building cutting-edge antimatter detectors at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Switzerland, the largest particle physics laboratory in the world.

These powerful tools and others aim to investigate whether the fundamental constants really are constant or if they change in time by tiny amounts; to detect subtle differences in the properties of matter and antimatter; and to test of fundamental symmetries in the search for physics beyond the Standard Model.

In other words, they explore the very limits of existence in order to understand the world better.

Today, MPG is among RIKEN’s top collaborators internationally. And the partnership is only becoming more important as we look to solve large-scale social issues, a challenge that demands robust international collaboration as well as cutting-edge tools such as RIKEN’s high-performance computing facilities.

The problems we hope to tackle include not only global warming, but aging societies, food security, and the rise of generative artificial intelligence.

At celebrations for the 40th anniversary of the formal research co-operation agreement signed by the two institutions in 1984, delegates discussed these issues and talked about expanding their collaborations as a result.

We would like to add to our joint work in the fields of physics and chemistry—which have been the mainstay until now—new projects in the life sciences, such as neuroscience, and in artificial intelligence. These areas will hopefully present bold new chances to make important breakthroughs with our old friends.

Box 1: Using precision measurements to look for new physics

An important ongoing collaboration between the two organisations is the Max Planck-RIKEN-PTB Center for Time, Constants and Fundamental Symmetries, which involves RIKEN and the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics, and another German partner, the PTB (Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt), the National Metrology Institute of Germany. The center is designed to foster collaborations between experimental groups in atomic physics, antimatter physics, nuclear physics, quantum optics and metrology. Its researchers are looking for new physics using ultra-sensitive measurement devices, such as particle-traps, lattice-, single ion-, and quantum logic-clocks, and magnetometers. Launched in 2018, the center has published more than 40 high-profile papers on topics ranging from improved metrology techniques to optical spectroscopy examinations of Th-229’s nuclear transitions, which could help scientists establish optical nuclear clocks. Other measurements at the center established 3He as a new standard for magnetometry; performed the most precise test of matter/antimatter symmetry; studied anomalous anti-gravity with antiprotons; and successfully implemented the first quantum-logic based spectroscopy with highly charged ions. Participating scientists have received more than ten research prizes and have attracted numerous additional grants, emphatically demonstrating the benefits of collaboration between such strong research institutions. —Stefan Ulmer, Chief Scientist, Fundamental Symmetries Laboratory, RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research

© 2024 CERN

Box 2: RIKEN in Europe

About one third of RIKEN’s collaborative research agreements involve institutions in Europe and roughly one quarter of non-Japanese personnel at RIKEN are from Europe. To support these important relationships and further promote collaborative research and innovation, RIKEN established a Europe Office in November 2018, following offices that opened in Singapore in 2006 and Beijing in 2010. The Europe Office is responsible for all of Europe and its surrounding regions, with a mission that includes promoting the enhancement of RIKEN’s research capacity and visibility through collaborative research, fostering brain circulation through personnel exchanges, and tackling global challenges together with European partners.

Located in the heart of the EU quarter in Brussels, the RIKEN Europe Office interacts with research organizations, higher education institutions, funding agencies, research intensive industries, policymakers and individual researchers and managers, including RIKEN alumni. Recent events held by the Europe Office include the RIKEN Europe Symposium 2024, which focused on organoid models for clinical research. —Toshiyasu Ichioka, Director, RIKEN Europe Office © 2024 RIKEN

Rate this article

About the author

Makiko Naka, Executive Director, RIKEN

Makiko Naka is an executive director at RIKEN. She is in charge of international affairs, communications, young researcher development, and diversity. Naka began her academic career in developmental psychology, which led to a speciality in investigative interviews with alleged child victims. Before joining RIKEN, she spent 14 years as a professor at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. She has published more than 200 papers or book chapters. Her papers have received awards from the Japanese Psychological Association in 2006 and from the Developmental Psychology Association in 2022. She also received the International Award of Merit from the Japanese Psychological Association in 2020.