Nov. 17, 2006 Research Highlight Biology

Smallest ever genome sequenced

Molecular biologists probe the minimum set of genes alive

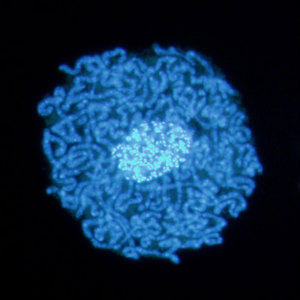

Figure 1: A stained bacteriocyte of the hackberry petiole gall psyllid packed with tubular Carsonella cells surrounding a central nucleus. Reprinted with permission from ref.1. Copyright (2006) AAAS.

Figure 1: A stained bacteriocyte of the hackberry petiole gall psyllid packed with tubular Carsonella cells surrounding a central nucleus. Reprinted with permission from ref.1. Copyright (2006) AAAS.

A collaborative team of researchers from RIKEN, other Japanese institutions, and the University of Arizona in the US has sequenced the smallest known genome—the DNA of a bacterium that lives inside the specially-tailored bacteriocyte cells of a sap-feeding insect (Fig. 1).

As reported in the journal Science1, the genome of Carsonella ruddii, a proteobacterium that lives inside the insect— called a hackberry petiole gall psyllid—contains fewer than 160,000 base pairs, which makes it about one-third the size of the next largest genome sequenced so far. The Carsonella genome has only 182 protein-coding genes, and is so compact that 164 of them overlap each other. Less than three per cent of the genome is non-coding DNA.

The study is an important step on the way to determining the minimum set of genes necessary for life. This, in itself, has significance for constructing synthetic genomes and building living organisms. The work is also relevant to understanding the evolution of the specialized membranous structures inside cells known as organelles. Chloroplasts, where photosynthesis takes place, and mitochondria, where energy production occurs, are both believed to have evolved from bacteria trapped inside primitive cells.

On analyzing the gene complement of Carsonella, the researchers discovered that more than half the genes were devoted to the production of proteins and their components, amino acids. But the genome entirely lacked genes for making the lipids, membranes, and genetic material essential for replication and survival.

Hence, reason the researchers, Carsonella is already involved in an obligatory symbiotic relationship with the gall psyllid, and well on the way to becoming incorporated as an organelle. The bacterium supplies the insect with essential amino acids lacking in its diet of plant sap, and the insect provides the bacterium with the compounds and molecular machinery to allow it to survive and replicate.

It is possible that several ancestral Carsonella genes were transferred to the genome of the gall psyllid and are now expressed by the nucleus of the cells in which the bacteria live, says lead author Atsushi Nakabachi from RIKEN’s Discovery Research Institute in Wako. “We are testing that hypothesis by trying to detect genes and gene products in the bacteriocyte cells which are relevant to Carsonella but are not found in the Carsonella genome.”

References

- 1. Nakabachi, A., Yamashita, A., Toh, H., Ishikawa, H., Dunbar, H., Moran, N. & Hattori, M. The 160-kilobase genome of the bacterial endosymbiont Carsonella. Science 314, 267 (2006). doi: 10.1126/science.1134196