Oct. 24, 2008 Research Highlight Biology

Brain waves

Electrical oscillations in one part of the brain suggest that it may interact with another to guide body movements

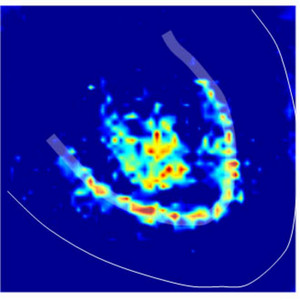

Figure 1: Localization of the brain waves around cerebellar neuron cell bodies (thick white line) and their axons (the area enclosed by this line). Reproduced from Ref. 1 © 2008, with permission from Elsevier

Figure 1: Localization of the brain waves around cerebellar neuron cell bodies (thick white line) and their axons (the area enclosed by this line). Reproduced from Ref. 1 © 2008, with permission from Elsevier

A seemingly simple action, such as picking up a pencil, actually involves complex communication between many parts of the central nervous system. Information about the pencil and its location enters the body through the eye, and eventually reaches a part of the brain called the somatosensory cortex. There, this information seems to be encoded as two types of brain waves: gamma waves, which oscillate 30–80 times per second, and very fast oscillations (VFOs), which oscillate 80–160 times per second. These brain rhythms may then be conveyed to other parts of the brain to initiate and control the action of reaching out an arm to pick up the pencil.

If other parts of the brain also produce gamma waves and VFOs, it is possible that these brain regions could receive these signals from the somatosensory cortex, and communicate with this or other portions of the cerebral cortex to control movements. In fact, recent work measuring brain waves from the cerebellum, the part of the brain responsible for motor learning, indicates that the cerebellum may communicate with the cerebral cortex to regulate movement. A team of researchers, including Steven Middleton and Thomas Knöpfel from the RIKEN Brain Science Institute (BSI), Wako, Miles Whittington from Newcastle University, United Kingdom, and Roger Traub, now at IBM in New York, report these findings in the journal Neuron1.

Tapping into brain waves

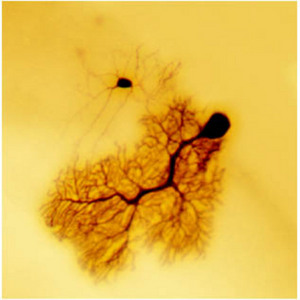

Figure 2: Dye-coupling between a cerebellar output neuron (bottom) and an interneuron (top). Reproduced from Ref. 1 © 2008, with permission from Elsevier

Figure 2: Dye-coupling between a cerebellar output neuron (bottom) and an interneuron (top). Reproduced from Ref. 1 © 2008, with permission from Elsevier

In slices from the mouse cerebellum that they had treated with nicotine, the researchers measured the frequency of oscillations using two methods: electrode recordings, and visualization of a voltage-sensitive dye (Fig. 1). By both methods, they found that the cerebellar oscillations were a mixture of gamma waves and VFOs. These waves were almost identical in frequency to oscillations others had measured in the cerebral cortex during the same experimental conditions. This frequency match suggests that the cerebellum and cerebral cortex may exchange signals to control movement.

The cerebral cortex contains many types of neurons that are both excitatory and inhibitory. The excitatory neurons, which use glutamate as their chemical neurotransmitter, play an important role in regulating the oscillations of the cerebral cortical neuronal network. The cerebellum also contains some excitatory (granule) cells, while the rest consists of inhibitory neurons, which use GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) as their neurotransmitter. The researchers demonstrated that the granule cells were not involved in generating the brain waves, so it was surprising that they observed these oscillations at all, since they had to have been generated by inhibitory neuronal populations only. The findings therefore indicate that brain areas with vastly different neuronal compositions can still produce similar rhythms.

Middleton, Knöpfel and colleagues also found another important difference between the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex. Oscillations in both brain regions can be triggered by activation of receptors for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine; however, the receptors in the cortex are so-called muscarinic receptors, which are not activated by nicotine, whereas the receptors in the cerebellum are triggered by nicotine. Furthermore, the cerebellar nicotine receptor that is acting to induce the brain waves seemed to be a ‘nonclassical’ nicotine receptor.

Unraveling neuronal communication

The network oscillations in the cerebral cortex occur due, in part, to gap junctions between cortical neurons, in which electrical activity in one cell can spread through channels that connect that neuron directly to its partner. The researchers also found many pieces of evidence that suggest that electrical connections also exist between cerebellar neurons.

First, they showed that a dye injected into a cerebellar output neuron, called the Purkinje cell, could diffuse to its neighboring local cerebellar interneuron, called a basket cell or a stellate cell (Fig. 2). Then, they blocked all chemical communication that occurs in the spaces between neurons, called ‘synaptic neurotransmission’, by removing calcium ions from the solution bathing the cerebellar slices, and still observed VFOs. Finally, they blocked gap junctions with a drug, and this manipulation was sufficient to block both the gamma waves and the VFOs. Their results suggest that direct electrical connections between cerebellar neurons may be one mechanism by which network oscillations are regulated.

Visualizing the source of brain waves

Middleton, Knöpfel and colleagues then used electrical and optical recordings to pinpoint the area of the cerebellum which was responsible for generating the gamma waves and the VFOs. “Optical voltage imaging is a technique for which the RIKEN BSI Laboratory for Neuronal Circuit Dynamics attains world-wide recognition,” says Knöpfel. ”We are expecting that the use of optical voltage imaging in this research field will increase over the coming years.”

The researchers also confirmed their findings in slices from the human cerebellum, suggesting that the data could also be relevant to motor function in humans. Because the oscillations were stimulated by nicotine, the findings imply that nicotine from cigarette smoking may have effects on motion—such as tremor—owing to effects on network oscillations in the cerebellum.

This research provides insight into how the cerebellum and cerebral cortex may communicate with each other to create, organize, and control movements. The researchers believe that their work establishes a new approach to the understanding of how the cerebellum handles information, suggesting that, as in cerebral cortex, oscillations are used for temporal coding of information.

“Startup of this exciting new research was made possible through a generous one-year grant from the directors’ fund of former BSI director Shunichi Amari,” explains Knöpfel. “While we have established the mechanisms underlying cerebellar oscillation generation, we now aim to study the behavioral correlates of these rhythms,” say Middleton and Knöpfel.

References

- 1. Middleton, S.J., Racca, C., Cunningham, M.O., Traub, R.D., Monyer, H., Knöpfel, T., Schofield, I.S., Jenkins, A. & Whittington, M.A. High-frequency network oscillations in cerebellar cortex. Neuron 58, 763–774 (2008). 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.030

About the Researcher

Steven Middleton and Thomas Knöpfel

Steven Middleton was born in Blackpool, UK, in 1981. After graduating in biochemistry from Lancaster University, UK, he obtained his PhD in 2005 at Leeds University, UK. After two years postdoctoral training at Newcastle University, UK, during which time he visited RIKEN Brain Science Institute (BSI) under a collaboration between Newcastle University and RIKEN BSI. In 2007 he joined the laboratory for Neuronal Circuit Dynamics at RIKEN BSI as a research scientist, where his research addresses the complex neuronal network dynamics seen in EEGs (electroencephalographs) that underlie cognitive processes.

Thomas Knöpfel was born in 1959 in Germany. He earned his MD in 1984 and his Master of Science in 1985, both from the University of Ulm. He then obtained his doctorate in physiology in 1985 and privatdozent (PD) in 1992, both from the University of Zurich, Switzerland. He was assistant (1985) and assistant professor (1989) at the Brain Science Institute, University of Zurich. In 1992, he became a team leader and project leader at Ciba-Geigy Pharmaceuticals (now Novartis). After working as a guest scientist at University College London in 1996, he joined the RIKEN Brain Science Institute as head of the Laboratory for Neuronal Circuit Dynamics in 1998.