May 22, 2015

Scientists discover new immune response that targets bacterial sugar coats

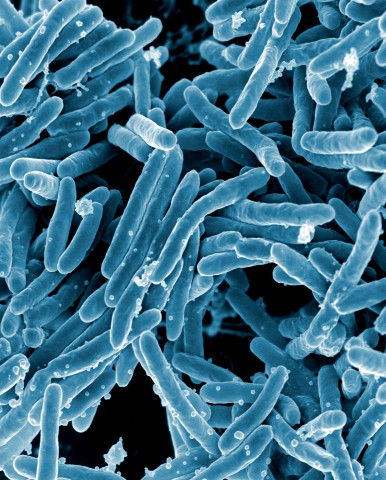

A joint effort by scientists in three leading research institutions—RIKEN, the Max Planck Society, and the Imperial College of London—recently revealed that a protein made in the human pancreas recognizes Mycobacterium tuberculosis,the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. The study, published in ChemBioChem, took advantage of each institute’s expertise in glycoscience—the study of complex carbohydrates—and as Peter Seeberger, director of the Max-Planck Institute for Colloids and Interfaces notes, “provides fundamental insights into how molecules in the tuberculosis bacteria are recognized by the human immune response.”

The protein ZG16p helps package enzymes in the pancreas and was first suspected to recognize bacteria because of its resemblance to other sugar-binding proteins. By using a microarray that fixes many different sugars onto a microchip, the team found that ZG16p preferentially binds to PIM1 and PIM2, two sugars that occur in M. tuberculosis. “Glycan arrays are very effective and often have a way of giving novel and unpredicted hits”, notes Ten Feizi, Director of the Glycosciences Laboratory at the Imperial College of London, “as we saw here, this can open up new and exciting avenues of research.”

In order to understand how the immune system recognizes these bacterial sugars in molecular detail, the team used special techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance. They identified two specific atoms in PIM1 and PIM2 as contact sites for ZG16p. Advanced computer modeling provided additional insights that help explain the binding of these complex molecules.

“Our finding is another example of the immense potential of the glycosciences,” says Yoshiki Yamaguchi from the RIKEN-Max Planck Joint Research Center, “the PIM-lectin interaction mode revealed in this study may be useful for the development of therapeutic antibodies or vaccines.”

The team feels their collaborative study is an ideal model for uncovering the biological roles of carbohydrate-binding proteins and the glycans they recognize. Explains Seeberger, “only the international collaboration between synthetic chemists at the Max-Planck Institute, structural scientists at RIKEN in Japan, and biochemists at the Imperial College London made this breakthrough possible.”