Feb. 22, 2013 Research Highlight Biology

Workings of the body clock

The neurotransmitter serotonin has been shown to link sleep–wake cycles with the body’s natural 24-hour cycle

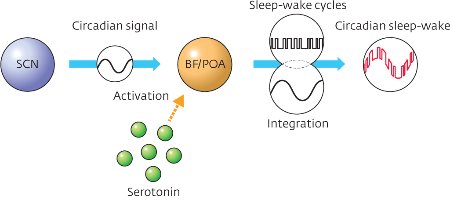

Figure 1: Serotonin links rhythmic activity in the basal forebrain and pre-optic area (BF/POA) to the circadian rhythm signalled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), allowing sleep-wake cycles to be regulated over 24 hours. © 2012 Hiroyuki Miyamoto, RIKEN Brain Science Institute

Figure 1: Serotonin links rhythmic activity in the basal forebrain and pre-optic area (BF/POA) to the circadian rhythm signalled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), allowing sleep-wake cycles to be regulated over 24 hours. © 2012 Hiroyuki Miyamoto, RIKEN Brain Science Institute

Almost all animals have a hard-wired ‘body-clock’ that controls biological function in cycles of approximately 24 hours. This is known as the circadian rhythm and, in mammals, it is controlled by signaling in a region of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The SCN regulates a number of functions, including hormonal secretion, metabolism, brain activity and sleep.

Areas of the brain close to the SCN—the basal forebrain and pre-optic area (BF/POA)—control short sleep–wake cycles. These short cycles, which are unevenly distributed across 24 hours, are regulated by the circadian rhythm. In order to maintain the overall circadian sleep pattern, these sleep–wake cycles must therefore be linked to the rhythm generated by the SCN. A team led by researchers at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Wako, has demonstrated that the neurotransmitter serotonin is the key to this link1.

The team measured neural firing in the SCN and BF/POA of rats to monitor rhythmic activity and looked at how this changed when serotonin levels were reduced. The neurotransmitter was depleted in two separate ways: either an enzyme called TSOI was injected to degrade the precursor of serotonin and prevent its production, or an inhibitor of serotonin production called PCPA was added. Both methods had the same effect.

“After serotonin depletion, sleep–wake cycles became fragmented,” said lead author Hiroyuki Miyamoto, “Sleep–wake phases were distributed throughout the day—that is, the circadian rhythm of sleep–wake cycles was lost.” Underlying this was a disruption of rhythmic neural activity in the BF/POA, caused specifically by the reduction of serotonin levels. The same effect was not seen in the SCN, however, meaning that the circadian rhythm was unaffected while sleep–wake cycles were disturbed. Blocking serotonergic transmission locally in the BF/POA was also sufficient to disrupt sleep–wake cycles. The researchers concluded that serotonin acts to link the two cycles (Fig. 1). “Since the BF/POA is a brain region that directly controls sleep–wake states, we think that coupling of the SCN and BF/POA activity rhythms by serotonin is critical for circadian sleep–wake rhythm,” says Miyamoto.

The findings may also help in understanding similar brain rhythms in humans and how they may contribute to disorders. “Similar mechanisms may also work in human brains,” says Miyamoto. “Dysfunction of the serotonin system has been implicated in depression and patients frequently complain of insomnia. Thus, our study may provide insights into the relationships between serotonin, sleep, circadian rhythms and depression.”

References

- 1. Miyamoto, H., Nakamaru-Ogiso, E., Hamada, K. & Hensch, T.K. Serotonergic integration of circadian clock and ultradian sleep-wake cycles. Journal of Neuroscience 32, 14794–14803 (2012). doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0793-12.2012