Dec. 8, 2017 Research Highlight Physics / Astronomy

Solar cells with a quantum shift

A quantum-mechanical way of generating photocurrents may help solar devices overcome existing inefficiencies

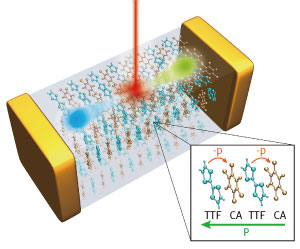

Figure 1: An organic charge-transfer complex can generate dissipation-free solar power thanks to quantum-based polarization effects. © 2017 RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science

Figure 1: An organic charge-transfer complex can generate dissipation-free solar power thanks to quantum-based polarization effects. © 2017 RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science

A much quicker, less wasteful way to extract current from solar cells that uses a quantum-mechanical process has been demonstrated by RIKEN researchers1.

When sunlight strikes a typical solar panel, it creates pairs of electrons and positively charged holes. Normally, an electric field is used to separate these charges and produce electrical power, but this approach requires charges that have high mobilities and lifetimes, which makes it hard to develop new photovoltaic materials.

An alternative approach for extracting current from solar cells involves exploiting the symmetry of the repeating structural units that make up crystals. Certain semiconductors lack ‘inversion’ symmetry—meaning that if their atoms are flipped about the center of the repeating unit, a different atomic arrangement will be produced.

For such semiconductors, light-induced transitions of charges to excited states become unbalanced, which creates a ‘shift current’ along a specific crystal direction. This shift current propagates rapidly and with less energy loss than a current generated by applying an electric field. But shift currents usually generate insufficient photovoltaic power for practical uses.

Now, Masao Nakamura from the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science and colleagues have overcome this shortcoming by using ferroelectric organic molecules that spontaneously separate their positive and negative charges. Because ferroelectric materials naturally disrupt inversion symmetry, they have potentially large shift currents—particularly when charge separation occurs due to quantum-mechanical differences in the covalent bonds holding a crystal together.

The team investigated an organic ferroelectric with strong quantum polarization to explore its shift-current capabilities. Composed of alternately stacked tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) and p-chloranil (CA) aromatic rings (Fig. 1), this complex undergoes instantaneous charge separation when cooled to around −200 degrees Celsius and is particularly sensitive to sunlight.

Masao Nakamura and co-workers have found how to reliably generate an ultra-efficient form of photoelectricity for next-generation solar cells. © 2017 RIKEN

Masao Nakamura and co-workers have found how to reliably generate an ultra-efficient form of photoelectricity for next-generation solar cells. © 2017 RIKEN

“Most ferroelectric materials need light with energy in the ultraviolet region to excite carriers over a large band gap,” says Nakamura. “With TTF–CA, the band gap is narrow and responds to visible and infrared light, which is really important for applications like solar cells.”

When the researchers measured the photovoltaic properties of the organic complex, they were taken aback by the amount of shift current generated—nearly ten times higher than comparable oxide ferroelectrics. The quantum-based charge transfer dramatically improved solar output power and allowed the current to travel as far as 200 micrometers before dissipating.

Because the shift-current effects in TTF–CA are so sizeable, Nakamura expects that it could be used as a platform to implement this photoelectric conversion in next-generation devices. “We’ll be looking at other ferroelectrics to try for room-temperature operation,” he says. “And we think we can improve extraction efficiency by employing thin-film device structures.”

Related contents

- Photovoltaics stand to profit from electronic ‘catastrophes’

- Working at the interface for future energy

- Multiplying solar harvests with ‘correlated’ technology

References

- 1. Nakamura, M., Horiuchi, S., Kagawa, F., Ogawa, N., Kurumaji, T., Tokura, Y. & Kawasaki, M. Shift current photovoltaic effect in a ferroelectric charge-transfer complex. Nature Communications 8, 281 (2017). doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00250-y